Galway – 1908

comad January 24th, 2016

From its beginning in 1861, ‘The Queen’ newspaper was recognized as ‘‘the foremost periodical for ladies of rank and breeding,’’ a distinction suggested by its full title: ‘The Queen, the Lady’s Newspaper and Court Chronicle’. Its founder, Samuel Beeton, designed the paper to ‘‘appeal to a readership of comfortably well off middle and upper-class ladies.’’

‘The Queen, The Lady’s Newspaper’

29th August 1908,

(page 399)

Galway — Lilian Emily Bland

The history of the town of Galway dates back to the days of Ptolemy, when it was known under the name of Magnata; but its days of prosperity, when it had a flourishing trade with Spain, are long since departed, and the Galway of today is a most picturesque jumble of ruins, side by side with with modern shops and houses.

From a photographic point of view the town is delightful, full of subjects for the camera in architecture and genre studies. Many of the houses are of Spanish origin, with the typical archways and courtyards of Spain, and the houses are warm in colour, deep yellows, reds, or blue, and, of course a great deal of whitewash which takes such exquisite tints in sunshine and shadow.

The women still wear the short, rough, scarlet petticoats, but the blue shawl is superceded by black and coloured shawls, which in line, if not in colour, are equally picturesque. Many of the women are, however, very shy about being photographed, and hide their faces in their shawls, which, as they are for the most part very plain, matters the less. One sees very few young girls (I think most of them emigrate), but the town is full of old women, with faces a deep yellow, from the atmosphere of peat smoke in which they live.

The most delightful part of the town is the Claddagh (pron. Clad-ah), a colony of fishermen’s houses, tiny, whitewashed, thatched huts. There is one street or road through the Claddagh, but otherwise the rest of the colony is built any way it pleased the owners, without any idea of line or order, and, of course, the sanitary arrangements are nil, and from time to time there are bad outbreaks of fever. Until recent years the Claddagh folk kept entirely to themselves, and had their own laws and elected a king, who settled all disputes; they are still very conservative and superstitious, and dislike any innovations.

(It was considered very bad luck to pick up any tool unrelated to fishing, i.e farming tools such as spades or ploughs. Any man who did was banished from the village. The sight of a red-haired woman on the way out to sea would make any fisherman quickly turn around and abandon their sea-faring plans for the day, as would the sight of a hare. No boat left for the sea without oat-cake, salt and ashes. However, if a crow flew over the boat and cawed, then that was considered a good omen.)

The first recorded King was Very Rev. Fr. Thomas D Folan

Michael Lynskey is the current King (January 2016).

From June to August the herring and mackerel come into the bay, but not a boat will go out until the bishop has been rowed out and poured holy oil on the water and blessed the bay. Occasionally the bishop and the fish are not both in Galway together, and then the fishermen look on and the fish depart again, for it would not be lucky to take a boat out.

The river Corrib rushes through the town; starting beyond the first bridge with a weir and splendid salmon pool, it turns many mill wheels before it reaches the bay. Beyond the salmon pool it winds its way up to Lough Corrib, and there is a beautiful trip up the lake some thirty or forty miles (48 – 64 km) to Cong, the steamer leaving Galway every day and returning the next day. Lough Corrib is, of course, famous for its trout fishing. Near the mouth of the river, between Spanish Parade and the Claddagh, the salmon are netted, and eight men are working the nets all day long. There are hundreds of gulls on the river, and the other day while I was watching them, each dainty little black-headed gull was swooping down and rising again with a young eel, or elver, as they are called, in its beak; These elvers come up the river in thousands from the sea and the gulls have a fine feast. In May the boats go out and collect seaweed off the rocks which is sold at from 15 shillings to 1 pound (20 shillings) a load to farmers inland for manure.

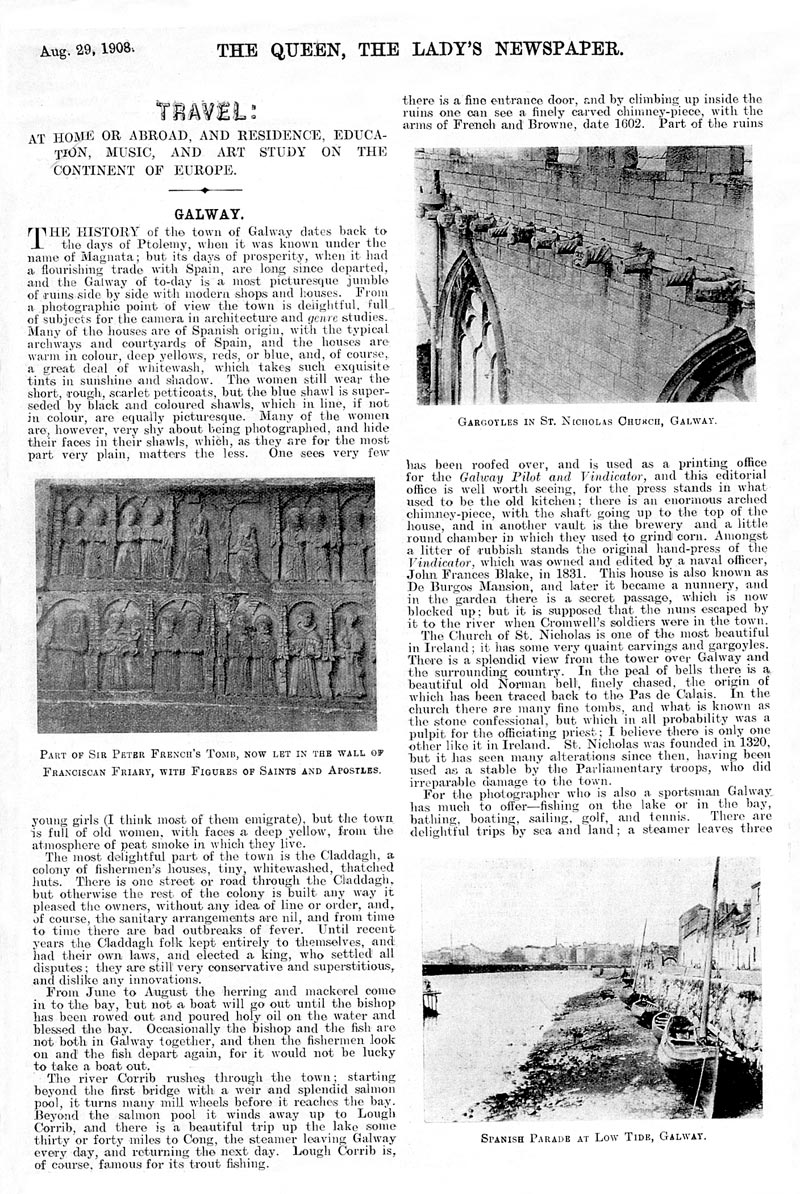

There are some of the most beautiful bits of stone carving on some of the old ruins and in odd side streets, and one fine example is Lynch’s mansion, which is well preserved. What is equally interesting , and apparantly unknown, is the old graveyard behind the Franciscan Friary; this was the burying place for centuries of the old Galway families; it is an overgrown confusion of weeds and tombstones, many of which have fallen in. In the outside wall of the friary are two carved panels of Sir Peter French’s tomb (died February 1631), which was broken up by Cromwell’s soldiers, and it is now getting much worn by the weather.

The garrison under Peter Stubbers destroyed the monuments throughout the town, and desecrated the tombs in search of treasure. The crucifixes in the Church of St. Nicholas and in the Abbey were smashed as also were the marbles with carvings of the Crucifixion. “Amongst the rest Sir Peter Frenche’s tomb, or monument, guilted with gold, and carved in fine marble, which stood in the Abbey, and cost in the building thereof £5,000 in 1653 by Lady Mary Brown, a virtuous woman, wife to the said Sir Peter Frenche, and which monument was converted by the governor of the town into a chimney piece, and the rest of the stones sent beyond seas, and there sold for money by the governor, and the said tomb left open for dogs to drag and eat the dead corpse there interred. They likewise razed down (demolished) the king’s arms, and converted the churches and abbeys to stables, and divine books were broken up, and put under goods, wares, tobacco, etc., etc., they being for the most part illiterate and covetous to hoard money, to the great ruin of the poor inhabitants, without regard to conscience or observance of public faith.”

“In June, Charles Fleetwood, Lord Deputy of Ireland, took his circuit and came to Galway, where he gave a definite sentence for removal of the old inhabitants of Galway; which order was immediately sent from Dublin and executed contrary to their conditions and articles. Lieutenant Colonel Humphry Hurd, Deputy Governor of Galway, and Colonel Stubbers, issued an order to prohibit the wearing of the mantle, (heavy wool blanket), which he enforced with such severity, that it came to be everywhere laid aside, and they cut a laughable figure, who having nothing but the mantle to cover their upper parts, ran half naked about the town, shrouded in table cloths, pieces of tapestry and rags of all colours and form, so that they looked as if they had escaped from bedlam.”

(extract from ‘A Statistical and Agricultural Survey of the County of Galway’ by Hely Dutton pub. 1824 – page 288)

Sir Peter French’s house, or, rather, the ruins of it, are in Market-street; there is a fine entrance door, and by climbing up inside the ruins one can see a finely carved chimney-piece, with the arms of French and Browne, date 1602. Part of the ruins has been roofed over, and is used as a printing office for the Galway Pilot and Vindicator, and this editorial office is well worth seeing, for the press stands in what used to be the old kitchen; There is an enormous arched chimney-piece, with a shaft going up to the top of the house, and in another vault is the brewery and a little round chamber in which they used to grind corn. Amongst a litter of rubbish stands the original hand press of the Vindicator, which was owned and edited by a naval officer, John Frances Blake, in 1831.

John Frances Blake died in 1864 aged 76 years and his passing was recorded in the ‘Clare Journal and Ennis Advertiser’ on 24 March that year.

“Mr. Blake, proprietor of the ‘Galway Vindicator’ was highly esteemed by his fellow-citizens, of whose interest and prosperity his able paper was ever the constant and unflinching advocate, as it was the uncompromising foe of anti-national and anti-Irish men and measures.”

This house is also known as De Burgos Mansion, and later it became a nunnery, and in the garden there is a secret passage, which is now blocked up; but it is supposed that the nuns escaped by it to the river when Cromwell’s soldiers were in the town.

The church of St Nicolas is one of the most beautiful in Ireland; it has some very quaint carvings and gargoyles. There is a splendid view from the tower over Galway and the surrounding country. In the peal of bells there is a beautiful old Norman bell, finely chased, the origin of which has been traced back to the Pas de Calais. In the church there are many fine tombs, and what is known as the stone confessional, but which in all probability was a pulpit for the officiating priest; I believe there is only one other like it in Ireland. St Nicholas was founded in 1320 but has seen many alterations since then, having been used as a stable by Parlimentary troops, who did irreparable damage to the town.

For the photographer who is also a sportsman, Galway has much to offer – fishing on the lake or in the bay, bathing, boating, sailing, golf and tennis. There are delightful trips by sea and land; a steamer leaves three days a week for Arran. There are a few hotels and boarding houses in Galway but the most comfortable house to stay in is Daly’s Fort, at Salthill, run by an Irish lady, and the terms are very moderate; this is close to the golf links and bathing shore, and a train brings one out from the town in fifteen minutes. At Salthill there is a splendid view over the bay and the coast of Clare.

_____________________________________________

- Comments(0)