Flight aero weekly 17th December 1910

comad September 16th, 2015

THE “MAYFLY” – THE FIRST IRISH BIPLANE.

and how she was built

By LILIAN E. BLAND

page 1025

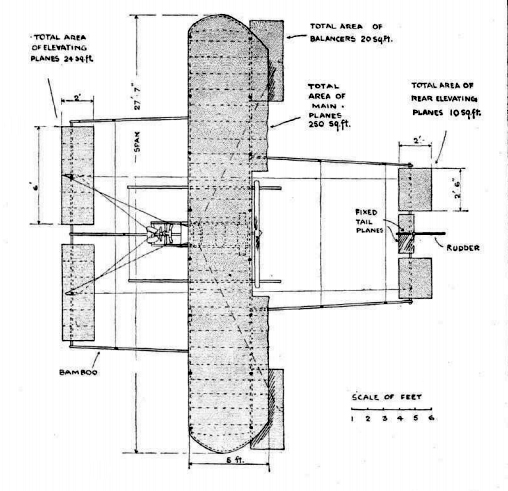

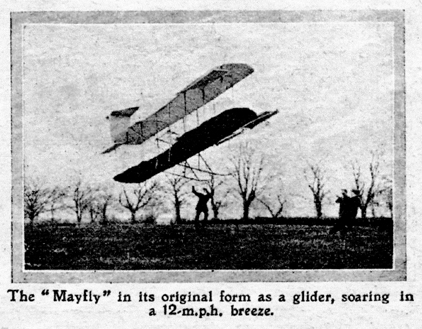

In view of the considerable interest which has been taken in my biplane which has gradually been evolved from a glider, I have, at the request of the Editor, written the following description of it : As the principal dimensions of the machine are given in the scale drawings, it will be unnecessary to repeat them here . The wood used for the main spars is ash, the curve of the wing tips being steam bent. The ribs and stanchions are of spruce, the outriggers of bamboo, the skids of ash, and the engine bed of American elm.

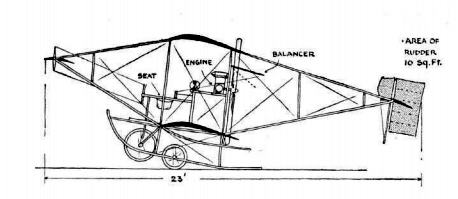

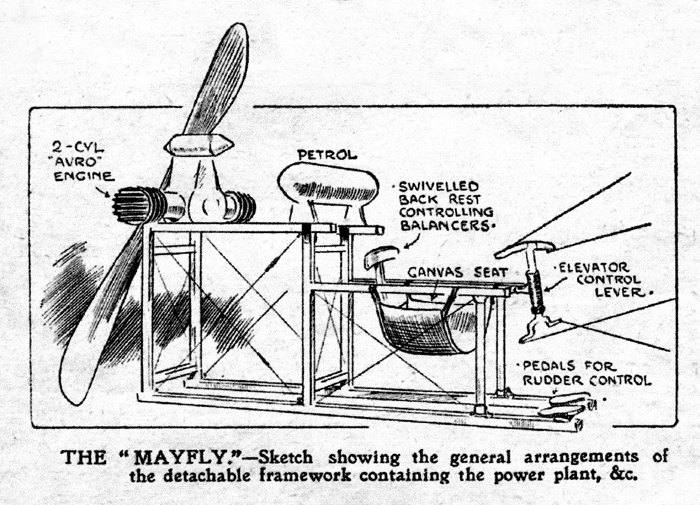

This engine bed is really a separate chassis set across the main spars, to which it is clipped; stays run from the rear spar to the chassis, which is also wired out to the upper and lower spars, so that it would be impossible for the engine to shift unless the whole machine were wrecked. Additional strength is also given to the wings by the wiring. The chassis carries the tank and the pilots seat, the latter being slung by four straps. In front of the seat, which is enclosed on all sides so that it is impossible to fall out of it, is the bar for the elevator control. The whole chassis can be removed in one piece either with or without the engine, which is held in place by four bolts.

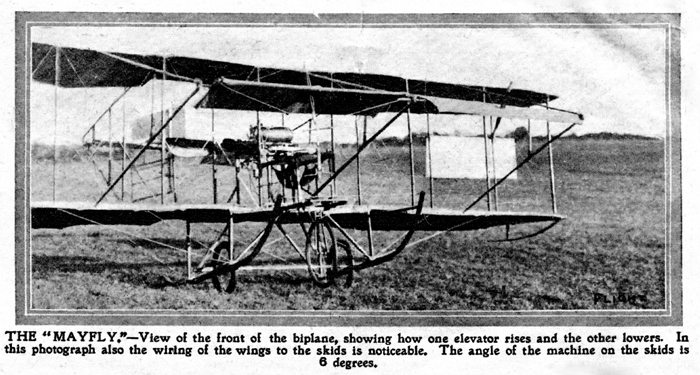

The controls consist of a bicycle handle bar which rocks and turns. Turning the handle to the right raises the right hand elevator and depresses the left, the connecting wires being crossed. The elevators are connected to the horizontal tail planes, which work in the opposite direction to the elevators; all controls are double, wire and strong waterproof whipcord. The balancing planes which are hinged to the rear stanchions are controlled by the back of the seat, leaning to the right pulls down the right hand balancer and vice versa. The vertical rudder is worked by pedals. The engine controls consist of a butterfly valve which regulates the petrol supply, an air throttle, and a lever to the magneto, while when starting one cylinder is cut out. All these controls may sound complicated, but in practice they are quite simple to work, and I think it is a great advantage to have the engine and aeroplane under complete control, as it is not always necessary to run the engine all out.

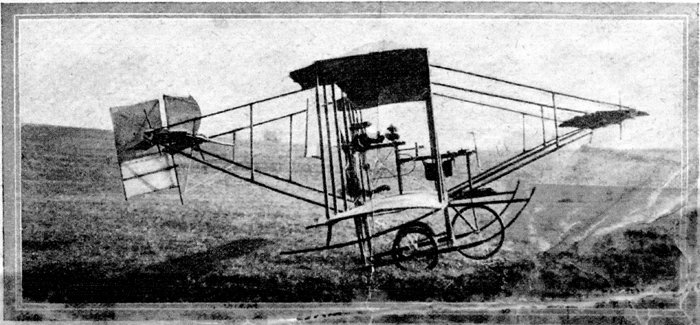

This side view shows the machine as she now is, (Dec 1910) but in the new tail Miss Bland contemplates fitting, the fin in front of the rudder will not be used

Flightglobal archives

When the engine starts, the draught from the propeller lifts the tail and the tip of the skids off the ground, and the machine balances on the two wheels; the third wheel in front only comes into action over rough ground, and is to prevent the machine from going on to her nose; it answers the purpose admirably, as my practice ground is rough grass with ridge and furrow, which on hunting principles I take at a slant.

I have wasted much time in trying to run the machine on ball-bearing wheels and spindles, fitted with various springs, rubber bands &c., none of which were satisfactory. The spindles were always bending or breaking, and the wheels are now rebuilt on to 7 inch (18cm) hubs, which run on the axle. The axle is clipped to the skids and the only spring is that afforded by the Palmer tyres.

The construction of the machine is more or less of the usual type, but the trailing edge and wing tips are more flexible. Originally steamed ribs were used but were later discarded, as they did not keep their proper curve ; The present ribs are cut out solid to the correct curve for the lower surface of the rib, and are given a flatter curve on the top, while they are bored out for the sake of lightness.

The double surface of fabric is laced on, a method which allows one to make any alterations without spoiling the fabric, and also it can be tightened up when it stretches. The machine was out for four months in the open, including the wettest August we have had for years, and the fabric is still waterproof, and except that it looks very dirty, is as good as when it was put on. The machine was tethered with three ropes fore and aft, from the main spars, and with her back to the south, and the west wind blowing along the span, she rode out several gales in safety.

I should not advise any amateurs to commence building aeroplanes unless they have plenty of spare time and money, but there are nevertheless many people who like myself have the time, but lack the necessary L.S.D. (pounds, shillings and pence)

As the result of my experience I am certain that the only way to build an aeroplane cheaply is to put the best of everything into it. Eyebolts, I think, should be hand turned with good solid heads, and, needless to add, wire-strainer eyes should be strong, and the threads properly cut. Castle nuts or patent locking washers of some kind should be used to prevent the nuts working loose with the vibration. I may say that got all my wire, bolts, &c., from Messrs. A. V. Roe and Co., and was very well satisfied. The actual cost of a biplane is not very serious, as sufficient good wood (in the rough) costs about £3 or £4. With regard to the fabric, I now use unbleached calico, which is 6 ft. (183cm) wide and costs 9d a yard. The running gear will cost anything from £6 upwards. The engine, as everyone knows, is the most serious item. My own machine has a 20 h.p. engine, and the expenses have not yet amounted to £200, although the machine has been practically rebuilt, has had two propellers, several pairs of skids, three different tails, &c. It should be borne in mind, however that this means doing all the work oneself, which is not altogether a disadvantage.

My first propeller was broken by some wires snapping from the vibration of the engine, and when the second propeller had had some narrow shaves from the same cause I tied all the wires back, so that when it snapped it could do no further harm; the break was always at the bend on the loop. Unless the wire is silver plated it has to be continually cleaned to keep it free from rust and as many wires are difficult to get at to clean it is a good plan to paint them. I use a good black enamel for all the clips. All the woodwork is copal varnished to protect it.

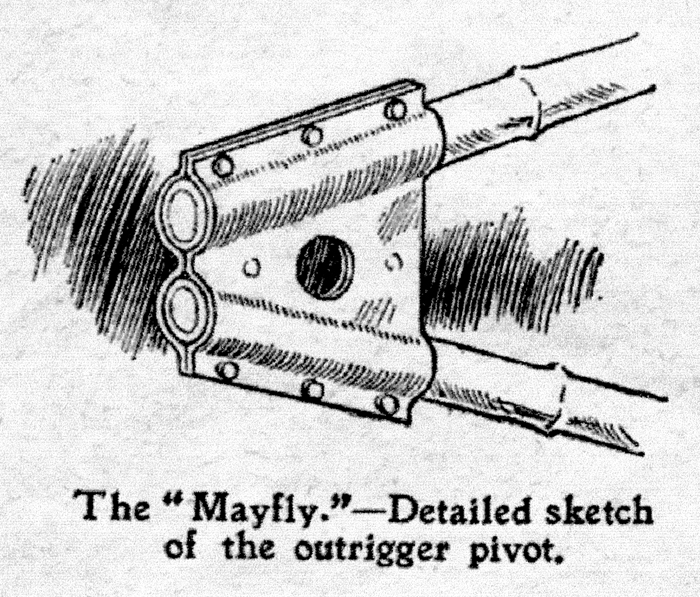

Bamboos should be carefully selected, the section of the cane being thick and round, and one generally has to sort through 20 or more canes to find one good one. The bamboos also get a coat of varnish, the ends have an air hole drilled, before the plug is driven in. A piece of cycle tube with one end flattened to make the necessary clip, is slipped over the bamboo, and riveted on. The other clips, &c., are made of different guages of hoop iron or steel.

The tank and carburettor float are placed across the span of the machine, so that the fore and, aft tilt does not interfere with the petrol supply when the tank is getting empty; tanks are made now with two cocks leading to the tube, which gets over this difficulty where the fuel is fed by gravity.

As to the actual flying of a machine, I am not a good enough pilot yet to give much advice, and my own machine is the only one I have been on. She rolls considerably until she gets up speed, and I imagine all machines do the same. As this is the natural action of the beast when one sits still, it is not necessary to try and balance the roll. If the balancing planes fail to right the machine quick enough, the vertical rudder can always be relied on to do so. One can learn a great deal by watching good pilots. Unfortunately there are none in Ireland at present, but I have been fortunate in seeing Farman, Paulhan, and Latham, all masters of the art.

Certainly it is, the finest sport in the world, and well worth all the hard work, but there is still plenty of room for improvement both in the aeroplanes, engines and propellers. I imagine one of the best types of aeroplane would be a tandem monoplane, in which the wings would be used for balancing and elevation.

To sum up the various points one has to settle before starting the construction of a machine :-

Firstly. – A place to fly it in. Bad ground is waste of time and takes much longer to learn on.

Secondly. – The engine, if of low h.p., the aeroplane must be light and have large area to weight.

Thirdly.- The placing of engine and pilot, and whether main planes will carry all the weight, &c.

Fourthly.- To draw out every detail to scale, and if trying an original design, to make a good-sized model, and see if any new point in controls or design is going to work as it is intended.

Fifthly.- Design the machine so that it can be easily taken to pieces for transport, &c. (by turning the skids round, my machine will wheel along any road when the outriggers are taken off).

In conclusion, I should be glad to get orders either for gliders or full-sized machines, and provided I can use my own designs, I will guarantee that the machines will glide or fly, that the work and quality will be of the best, but the engine and propeller must be reasonably efficient, otherwise it is only waste of time.

_________________________________

- Comments(0)